Applied or “college level” courses are offered in the vast majority of high schools in Ontario, including Sudbury's Lo-Ellen Park. Lo-Ellen provides four types of courses: International Baccalaureate, academic, applied, and locally developed. According to the Rainbow District School Board website, applied level classes are designed to cater to students who “Achieve level 2 or above in core subject areas; Demonstrate a learning style suited to hands-on, practical learning; [and] Require more specific, teacher-directed instruction.” Applied is supposedly intended for students with either a strong interest in college-type courses, or students who have been struggling (or are predicted to struggle) in the academic level and require more specific learning environments.

This description, however, fails to make clear who actually ends up in applied courses: Students from lower-income families, Native students, children of undereducated parents, and recent immigrants make up the bulk of the applied populace. And most of these students feel that they would be capable of taking academic classes if more specialized support was provided -- it’s only inequity that’s holding them back from being able to make a real choice between university and college.

The Trouble with the Classes

In literature and popular culture, high schools are often used -- largely to comedic effect -- as microcosms for society in general. Despite the cliché, applied level classes follow in line with a negative societal trend. Globally and in Canada, it has been shown that people from working- and lower-middle-class families are more likely to go on to work in the trades or other “blue-collar” jobs. How does this link into our high schools? Statistics Canada has said that “students from well-to-do families are more likely to attend high schools that have a high propensity to produce university-bound students.” In short, students from higher income families are more likely to attend university rather than attend college, enter an apprenticeship, or simply join the workforce with a high school diploma.

Certainly, there is no problem with students wanting to attend college. Some students have actively chosen to be in applied because they have no intention of attending university, and they should be supported in this choice. In fact, Canada is in dire need of trade workers, and would benefit from a higher college population. The problem lies in the fact that a large portion of students are having their choices limited to college by their economic status. The need for trade workers is no excuse for this polarization.

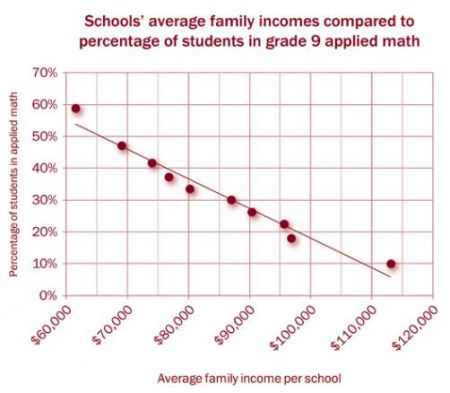

Starting from elementary school, lower income populations are less likely to have the choice to attend university. The numbers are telling, as was shown in a 2013 report by PeopleForEducation: In low income schools, 45% of students are in applied level classes, while higher-income schools have an applied average of 18%. Despite the increased provincial grades average, it is clear the school system is deeply flawed and polarized. The graph from the PeopleForEducation report presented here as Figure 1 illustrates the issue clearly.

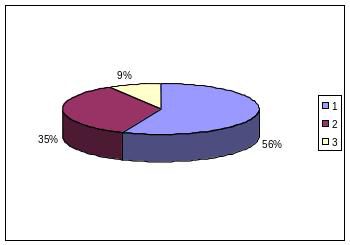

In the same report, other populations, such as Aboriginal peoples, were also shown to be over-represented in the applied population. Again, the numbers are telling:

“In the 10% of schools with the highest concentration of students taking applied mathematics in Grade 9, relative to the 10% of schools with the lowest concentration of such students, the students were:

• 2½ times as likely to have parents who did not finishhigh school;

• almost two-thirds less likely to have parents whoattended university;

• from families where the average family income wasalmost half that of the schools with the smallest proportion of students taking applied mathematics;

• more than three times (3.7 times) as likely to be Aboriginal;

and

• nearly twice as likely to be English Language Learners.”

How can this problem be avoided? There is no simple answer; the root of the polarization isn’t entirely due to any one factor. Home environment, school environment, parental or peer influences -- these are also factors that have made things the way they are today. This, however, doesn’t stop the school board from making changes that will benefit the situation.

What is the solution? And can the school board do it?

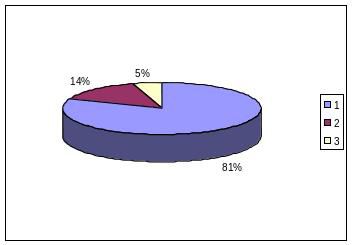

Applied is associated with many deep flaws, but despite its faults, simply removing the program would not be a wise decision. Many students feel that applied is a good option for those who want to have hands-on learning and are firmly set on college. More than 80% of the 27 applied students at Lo-Ellen Park surveyed for this article agreed that that applied courses should continue to be offered (see Figure 3). It is also true that many students in applied are unwilling to enter academic because they are comfortable in their learning environment and feel that they would be discouraged by the more theoretical curriculum. As mentioned before, it is also unfair to discourage those who are firmly set on attending college. However, rethinking how the system works is necessary, so that the school board can provide the personalized support students need.

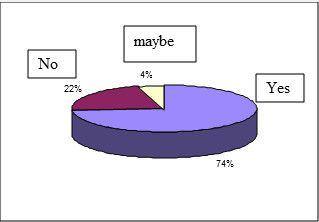

Many students that were recommended to enter applied level courses because of lagging grades in academic feel that they could be capable of finding success in a higher education level if more support was provided. Among the applied students surveyed at Lo-Ellen, 74% felt that they would have the ability to flourish in academic if more personalized support was received (see Figure 4). Having tutored students in the past, it is clear to me how much difference even an hour or so of intensive one-on-one support can make. Some students taking the survey claimed they were in applied because they were “stupid.” This is, of course, untrue: if help is given early enough, we can all end up in the same place. I believe that this scenario is theoretically possible.

The school board has demonstrated that it is capable of providing effective personalized support. For example, the school board has been quite successful in designing an approach for students with special needs. Every school in Ontario must have an Identification, Placement, and Review Committee (IPRC) comprised of three individuals who are qualified to “identify the areas of the student’s exceptionality, according to the categories and definitions of exceptionalities provided by the Ministry of Education,” as described by the Ontario Ministry for Education. “Exceptionality” is a long-winded term for the specific learning needs of students, particularly of students with learning or mental disabilities.

Of course, the student population who receives IPRC classification and an Individual Education Plan is a scarce minority. This strategy has, however, been shown to be successful and efficient when properly implemented. (Special education teachers are in short supply, but this is another issue). I believe that a similar philosophy can be applied to students at large: That is, to provide a much higher level of specialized support, be it one-on-one presence, an extra helper in the classroom, or simply a better understanding of student needs.

It is also clear that individual schools have the power to make internal change (albeit not extensive societal change) if the willpower is present. The previously cited 2013 study by PeopleForEducation states that “91% of principals report students transfer from applied to academic ‘never’ or ‘not very often’. Interestingly, in 9% of schools, principals report that students transfer ‘often’, which suggests that school-level policies have a significant effect on students’ decisions to transfer.” This shows that a few clear changes, such as ones geared towards ideas like the ones presented here, can make a large difference to the decisions and capabilities of students. In other words, student environments can be radically altered to help improve the situation. Ultimately, the best-case scenario would be to provide the choice of both college and university for every student.

If tutors, educational assistants, or a similar type of classroom support was funded from elementary school and forwards, it might be imaginable to have a grade 9 where we all start from a similar learning level, like we did in JK or SK. Over a single generation, the school board could help equalize a social injustice.

This is the vision I want to present, but I recognize there is a great deal about it that is unrealistic. Actual funding for the ideas presented here is unfeasible, requiring money the school board doesn’t have and a shift in government budget values. As mentioned before, this issue reaches beyond the school board. The board can make change, but a general societal values shift will have to go along with it if it’s going to happen. What this opinion piece seeks to show is simply a statement: there are serious flaws at the heart of applied. And something should definitely be done about it.

Damián Arteca is a grade 12 high school student who attends Lo-Ellen Park Secondary School.

The following are quotes from the 27 Lo-Ellen Park students in applied courses who were surveyed for this article. Some responses were positive, other negative:

-“The applied pathway still leads me to my career goal”

-“Probably would have dropped out [if applied wasn’t an option]. It’s to much of an expectation to put on a lot of students”

-“[I am capable of being in academic because] if I tryed my hardest, I can achieve. ‘I believe I can achieve.’”

-“[if applied didn’t exist] I don’t even know if I would pass”

-“All kids should have the choice to at least try academic”

-“The principal didn’t even tell me that she put me in applied. I wanted to go into academic”

-In answer to, ‘what level of support would you say you received?’ : “What support?”

-“In academic I tried…on a test and passed with a 95%”

-“I have the ability to become better”

-“I had a tutor. He helped. But not enough.”

-In response to ‘Why are you in applied courses rather than academic?’: “I’m stupid.”

-“Some people aren't smart enough for academic classes”